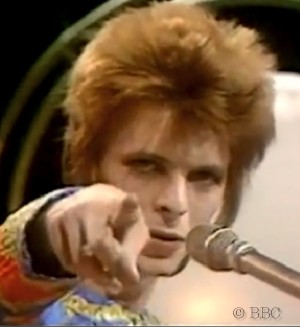

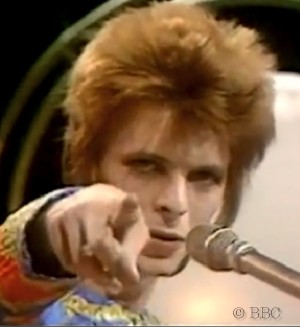

The moment the earth tilted July 6, 1972: During Starman on Top of the Pops, David Bowie drapes his arm around the shoulder of Mick Ronson. Video © BBC

❚ WHO DARES DEFINE GLAM ROCK? Almost nobody agrees what it means, even as we celebrate the 40th anniversary of glam’s birth, but that isn’t going to stop many of its prime movers lighting a few squibs in a thrilling and meticulous Ten Alps documentary titled The Glory of Glam†† across two hours on BBC Radio 2 tonight and tomorrow (iPlayer for a further week). This thorough analysis has been badly needed since the term glam became a rubbish-bin into which gets thrown anything brash, theatrical and shiny – such as shock-rock, metal and goth. The problem glam suffers is that the tat needs to be accounted for, then set aside, especially after you’ve waded through yards of tosh at Wikipedia penned by American sociologists out of their depth in this entirely British phenomenon.

Glam rock came cloaked in sequins, satin and unmasculine flamboyance. Its touchstones – alienation, decadence, self-invention and sexual transgression – most certainly went on to shape the UK’s fashion pop of the 80s, and glam’s pioneers were pillars of inspiration to the New Romantics. Even though glam banished the guitar solo and the drum break, it fuelled as much a fashion revolution as a musical one, if not more so, which many of its own practitioners didn’t get a handle on by merely pulling on their platform boots and zany top hats. Glam had deeper resonances than a sprinkling of glitter, and reached back into the traditions of theatre and Hollywood.

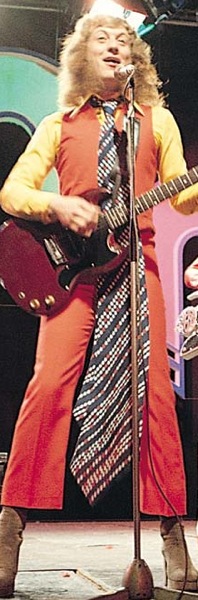

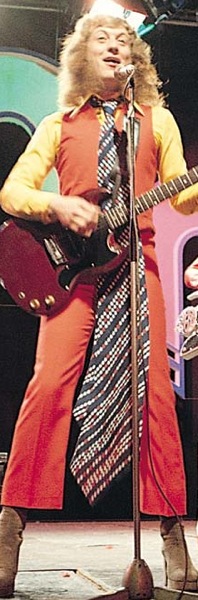

The pantomime version: mutton-chopped Noddy Holder of Slade

The Blitz Kids see no confusion. They draw a firm line between the distinctly fashion-driven imperatives of their own New Romantic style and the grotesque pantomime of the worst 70s glam-rockers. Certainly the Blitz Kids of 1980 admitted no connection with the chart-storming excess confected that year by Queen, whose origins lay in 60s psychedelia and heavy metal, still less make mention of Noddy Holder of Slade in the same breath as Ultravox, Visage, Depeche Mode or Spandau Ballet.

The 80s musician Gary Kemp, who narrates tonight’s documentary, writes in today’s Guardian: “I could spot the uncomfortable look on the face of a hefty northern bass player bursting from a turkey-foil jumpsuit worn simply to sell records. With Bowie, it was different: he had integrity. An effeminate, pale young man in eye shadow had somehow connected with working-class flash.”

Blitz fashion god Stephen Linard dismisses Slade’s avalanche of chart hits: “Even at 12, you knew Bolan and Bowie were special. Slade were just for fun, like Sweet and Gary Glitter – theirs was party music. The only reason I’d bought the first Gary Glitter album was because it was covered in glitter. Come on! Slade were hairy oiks from Birmingham, hideous sideburns, going bald on top. I plastered Roxy Music all over my bedroom because they were glamour. They had real transsexuals on the cover of their album. Everybody assumed Bryan Ferry’s girlfriend Amanda Lear was one!”

The indispensable Allmusic hits the mark when discussing Hunky Dory: “a kaleidoscopic array of pop styles, tied together only by Bowie’s sense of vision: a sweeping, cinematic mélange of high and low art, ambiguous sexuality, kitsch, and class . . . A touchstone for reinterpreting pop’s traditions.” There’s the nub of it: artsy pretension is out there a length ahead of beer-swilling mayhem. Any innovator at the Blitz club never loses sight of the origins of glam, whether in Bowie’s training with performance artist Lindsay Kemp, Eno’s experiments with electronica, Ferry as a walking ad for Antony Price’s luminous suits, and even Bolan’s obsessive eye for style instilled as a mod. To cap it all, in photographer Mick Rock’s opinion: “Bowie was good at being provocative, but the beauty was his lightness of touch.”

We are of course bang in the middle of the hoary old music-industry debate about art versus profits, innovation versus pomp.

Fortunately clarity is at hand. The next week boasts two landmarks on the timeline of pop that signal the dawn of glam and celebrate its immortals. July 1 is the 40th anniversary – the day in 1970 when Marc Bolan recorded the first glam-rock single, Ride a White Swan, though it took till year’s end and Top of the Pops to boost it to No 2 on the chart in January. A youthquake then erupted.

Ziggy sings: “So I picked on you-oo-oo”

By popular vote, however, the more resonant date is July 6, 1972. This Thursday is burnt into the souls of the specific generation who were to make good as popstars in the 1980s.

Songwriter and Spandau Ballet guitarist Gary Kemp speaks for many when he writes of the creation of Ziggy Stardust: “David Bowie’s seminal performance of Starman on Top of the Pops in 1972 became the benchmark by which we would for ever judge pop and youth culture. It was a cocksure swagger of pouting androgyny that appealed to pubescent working-class youth across Britain – a Britain still dominated by postwar austerity and weed-filled bomb sites. For us, the Swinging 60s had never happened; we were too busy watching telly.”

Kemp goes on: “The object of my passion had dyed orange hair and white nail varnish. Looking out from a tiny TV screen was a Mephistophelean messenger from the space age, a tinselled troubadour to give voice to my burgeoning sexuality. Pointing a manicured finger down the barrel of a BBC lens, he spoke to me: ‘I had to phone someone, so I picked on you.’ I had been chosen. Next to him, in superhero boots, his flaxen-haired buddy rode shotgun with a golden guitar. As my singing Starman draped his arm around him, I felt a frisson of desire and wanted to go to their planet. I had witnessed a visitation from a world of glitter. That night, I planned my future. After all, ‘If we can sparkle,’ he’d told me, ‘he may land tonight’.”

Bear in mind that at the time of White Swan, in 1970, our two pop idols had both been aged 23, and our pubescent audience of future Blitz Kids, typically born around 1959, were then 11. So they were rising to 13 by 1972 — detonation year for the glam explosion. That was when the careers of Roxy Music, Iggy Pop, Elton John and Alice Cooper all went critical in the UK, when Andrew Logan threw his first Alternative Miss World Contest, paving the way for the stage musical The Rocky Horror Show the following year [currently touring the UK till Dec 2010].

The Starman’s earth landing is the most influential song of Bowie’s many influential songs because it is seared on the memory of that generation of TV viewers. From Morrissey and Marr to Ian McCulloch, Neil Tennant and Siouxsie Sioux — all say this day changed their lives. For Michael Clark, who went on to lead an all-male dance company, it was a revelation because he’d only seen men touch each other when they were fighting, and suddenly he realised that there might be “kindred spirits” out there . . .

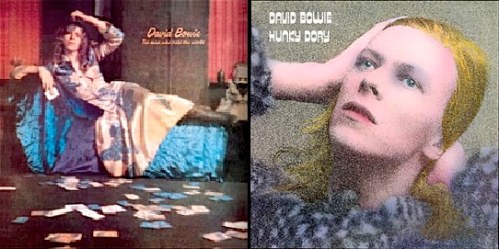

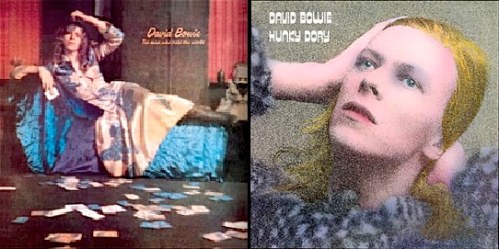

Bowie confronts camp: album sleeves for The Man Who Sold the World, and Hunky Dory

❚ MARC BOLAN AND DAVID BOWIE ARE INDISPUTABLY the progenitors of this flamboyant art-rock musical style at the dawn of the 70s, along with the Svengali who can claim much credit, Tony Visconti, the Brooklyn-born musician and producer who worked with the young Bolan and Bowie in London, with honourable mentions for Bryan Ferry and Brian Eno for the early Roxy Music. These voices are heard in the Radio 2 doc.

Angie Bowie says: “David and Marc liked each other very much and at certain times were great friends, but they were also bitter rivals.” As teenagers in the mid-60s they were both image-conscious suburban mods, then hippies, who experimented with styles from blues to psychedelia in search of their own pop moment. They first met while painting their shared manager’s office, and their paths constantly crossed at Bowie’s Beckenham Arts Lab and especially at Visconti’s flat in Earl’s Court, west London.

Bowie himself rather revelled in the rivalry, in May 1970 spoofing Bolan’s vocal style on Black Country Rock, a track on his album The Man Who Sold the World, recorded a couple of months before Bolan’s pivotal Swan. On the sleeve notes to Sound+Vision, Bowie recalls the day Bolan provided musical support while recording his Prettiest Star single at Trident Studios that January: “We had a sparring relationship… I don’t think we were talking to each other that day. I remember a very strange attitude in the studio. We were never in the same room at the same time. You could have cut the atmosphere with a knife.”

Both singers toyed with sexual ambiguity. While Bolan prettified himself into T.Rex, Bowie’s new wife Angie encouraged experiments in androgyny that led to the UK album cover where he wears what he called a “man dress” (though this image was replaced for the earlier US release in 1970).

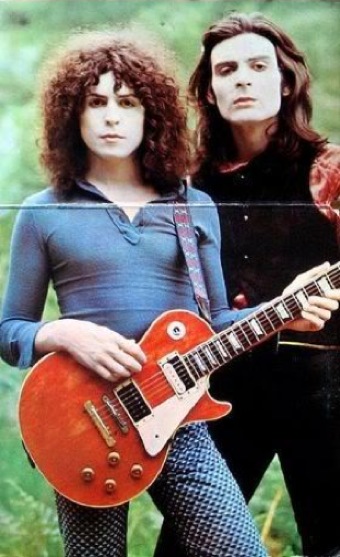

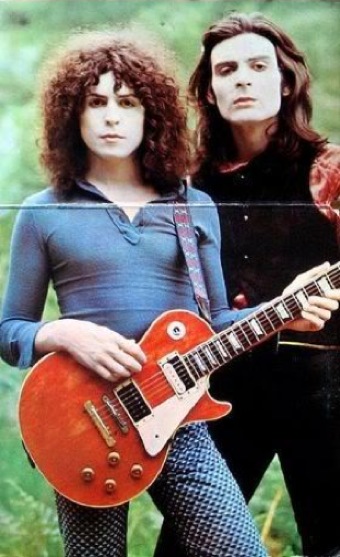

Transformed into T.Rex for the 1970 album: Bolan sports his new electric guitar, square-jawed and white-faced with Mickey Finn, in the Sussex garden of the photographer David Sanders’ mum

In their day, these were shock tactics – which still trigger fireworks in the art-versus-profits argument. So-called glam-rockers such as Slade and Sweet and Glitter weren’t into sexual role-play so much as pantomime and clowning, despite their figure-hugging satin.

What puts the music of Roxy Music, David Bowie and T.Rex in a different league? The elephant in the room is sex or, rather, sexual subversion. What is rock and roll if not almost entirely about that vertical expression of the famous horizontal desire? What is adolescence if it’s not at least partly about curiosity, confusion and the testing of boundaries? There’s no point in discussing glam rock without mentioning its implicit androgyny and the dangerous allure of unthreatening, feminine young men to adolescent audiences.

Kemp declares boldly in today’s Guardian of his Starman moment: “The first time I fell in love it was with a man.” And he notes: “Gender-bending was suddenly far more rebellious than drugs and violence.”

Brave words from any popstar in any era. Suzi Quatro observes in the radio doc: “All those men in eye shadow – you have to be very comfortable with your sexuality to play with it.” Even so, when a grown-up family man admits to an adolescent pash for a fey young man, it doesn’t necessarily make him gay, but it does take courage to admit.

❚ DESPITE THE CLIMATE OF PERMISSIVENESS the 60s had beqeathed, the word gay was taboo in public in 1970, even though the iconography was pretty blatant. As T.Rex, Bolan shed his folksy heritage for white-faced androgyny when twinned with Mickey Finn on their first album cover. Bowie adopted a Greta Garboesque pose for his portrait on Hunky Dory, and wore the “man-dress” by the Mayfair tailor Michael Fish on The Man Who Sold the World.

Bowie’s later admissions of “bisexuality” are well documented. In 2002 he told the American music magazine Blender: “I had no problem with people knowing I was bisexual.” In David Buckley’s 1999 book Strange Fascination, Bowie said that when he met his first wife, Angela Bowie, in 1969 they were “fucking the same bloke” and Buckley claimed the marriage had been cited as one of convenience for both.

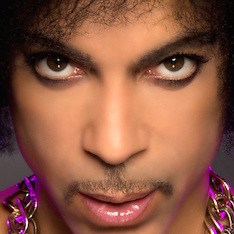

Sexual ambiguity: Bolan adopts the boa for T.Rex

There’s little or no contemporary evidence of Bolan’s now known bisexuality, except the eye witnesses. His manager during the late 60s, Simon Napier-Bell lays it out in the biog, The Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar by Mark Paytress (1992, revised 2006).

“Marc was more gay than straight. He had no hangups about sex,” says Napier-Bell, who lived in Lexham Gardens in west London at the time. “[Bolan] used to come round on the early-morning bus from his parents’ prefab in Wimbledon and get in bed with me in the morning. How can you manage anybody and not have a relationship with them? The sexual borders had completely collapsed by that time. Straight people thought they shouldn’t be straight. In fact, in the 60s, it was pretty difficult to have any sort of relationship with someone without it being sexual.”

An extreme perspective, perhaps, but “anything goes” was the motto for the coterie who subscribed to the Swinging London melting pot of hallucinatory drugs and louche morals.

In addition, bisexuality was growing in fashionability in the wake of the historic changes brought about by the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. Before then in the UK, gay activity was a jailable offence and hence highly blackmailable. It’s no coincidence that in 1971, a couple of years after New York’s Stonewall riots, the Campaign for Homosexual Equality emerged as the leading English gay rights organisation by staging its first march ending in a Trafalgar Square rally. By 1972 the explosion of glam-rock coincided with very visible expressions of gay liberation in the UK.

None of which implies that massed ranks of gay popstars leapt into the charts, though the totally closeted record business did ease the door open by a chink, whereas previously any hint of gay would spell death to a band’s career. The English star Dusty Springfield was extraordinarily brave at the age of 31 to entrust her coming out in 1970 to Ray Connolly in the Evening Standard, in an intense interview that remains a compelling read. (Ray told Shapersofthe80s: “I was a big fan and I actually didn’t want to ask her. She pushed me into it, saying, ‘There’s something else you should ask now… about the rumours’.”) It took Elton John till he was 41 to come out, first getting married in 1984 and divorcing four years later.

In the Radio 2 doc, Gene Simmons from Kiss sums up the social change that characterised the early 70s: “The great thing about glam was whether people thought you were gay or not didn’t matter. More was done to further different sexual preferences onstage in a rock band than all the commentaries from serious people, because there onstage, the way the old court jesters used to do in silly outfits, they were actually doing something serious, which in essence was saying, Be tolerant. The cool thing was that it was all cool.”

As for our immortals . . . Sadly we lost Bolan to a car crash when he was only 29. Had he been alive today he’d be the same age as Bowie, 63, give or take a few months. It’s challenging to speculate which of them might be shining the more brightly today as our totem of pop culture.

†† FOOTNOTE – This website has no connection with the makers of The Glory of Glam, and has since discovered the credit goes to producer Des Shaw and editor Chris O’Shaughnessy. If this documentary doesn’t win a Sony radio award, there’s no justice.

➢ 2013 update: Glam! The Performance of Style runs at Tate Liverpool Feb 8–May 12, 2013 – Well worth a day trip to Liverpool, this superbly curated exhibition explores 70s glam style and sensibility across the whole spectrum of painting, sculpture, installation art, film, photography and performance. The in-depth survey comes in two halves, drawing a clear distinction between the playful subversion of pop culture that characterised the British glam wave, and the American, which was driven much more profoundly by gender politics.

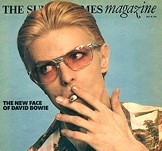

FRONT PAGE