➤ Britain’s favourite painter

discovers a truer way of seeing,

with help from Proust

AN HISTORIC INTERVIEW FROM 1983 – “Have you been to the cubism exhibition at the Tate?” David Hockney enthuses during a trip to London from his home in Los Angeles. “I’ve been seven times!” An impromptu tutorial ensues in which the influential English painter tests his new ideas.

It is extraordinary that this fortnight he spent in London is omitted from the artist’s official life story. The biographical timeline at Hockney’s own website (see foot of this page) makes no mention whatsoever of the events described here, or of the insight into cubism he reveals in this account, based on three long tape-recorded conversations with Hockney in the summer of 1983 . . .

➤ JUMP TO DISCOVERIES ON iPHONE AND iPAD

➤ JUMP TO 2012 EXHIBITION AT ROYAL ACADEMY

➤ JUMP TO 2012 EXPERIMENTS IN VIDEO

➤ JUMP TO 2013 HELLO TO CALIFORNIA

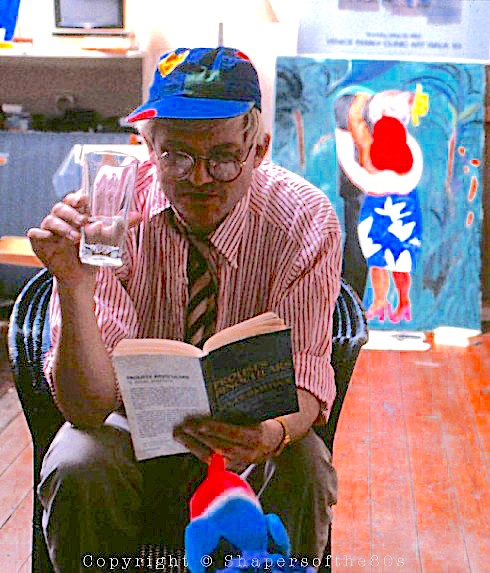

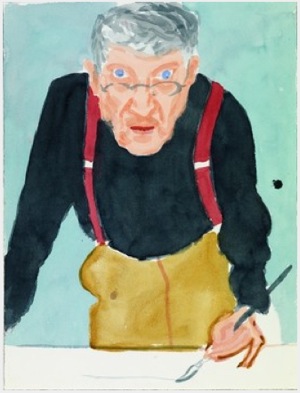

Hockney at his London studio, July 3, 1983: after a pause of two years, freshly painted canvases indicate the urgency with which he has resumed painting. Photographed © by Shapersofthe80s

An elision of two pieces first published in the Evening Standard,

July 8, 1983, and The Face, Sept 1983

❚ DAVID HOCKNEY HAS MADE A DISCOVERY so monumental that he calls it “a truer way of seeing” and says he can never look at pictures in the same way again. So when the artist regarded by some as a genius and by others as England’s most influential living painter adds, “The implications are staggering”, he is heralding a major revelation for us all.

“I’m getting very excited from what my experiments in photography have taught me,” Hockney says in his homely Yorkshire accent. “Whether it works for other people I don’t know, but television and movies look unreal to me now. My photographs are a criticism of all photography up to now. I think we have been swindled.”

We are at Kasmin’s Cork Street gallery during the hanging of his New Work With A Camera which opened on Tuesday. In the week of his 46th birthday, Hockney is eager to discuss for the first time the dramatic adventure that the past 18 months behind a camera have become, but which “the critics haven’t been too bright about”.

“All these photographs are about closeness,” he says, enthusing beside one view seen from the driving seat of a Mercedes. “I am sat at the wheel of the car and look how close it seems. It comes right to you. You could be sitting there. But you never see advertisements for cars like that.”

The collaged composition certainly creates a powerful three-dimensional effect of thrusting you on to the highway in California, where he has made his home. He moves to an 11-foot-wide photographic composite of the Grand Canyon which feels positively giddying as we peer over the railings.

Click to reveal full image — detail from The Grand Canyon South Rim with Rail, Arizona, Oct 1982 © David Hockney. Photographic collage, in the artist’s original frame 43 x 137 inches. Last sold at auction by Phillips Oct 2, 2012

These pictures are in another realm from the Polaroid arrays he showed last summer – what he calls “joiners”. The new ones are much more prismatic in composition. At first sight a picture seems to consist of one photograph cut up into perhaps 100 pieces. In fact these are individual postcard-sized shots, each giving a different angle on the scene, as Hockney has turned his body and snapped with his camera to left and right, up and down. In one, Christopher Isherwood is seen talking to a friend in his Santa Monica home and in the part of the room where Isherwood sits there are about five shots of his head.

Why is the effect more fascinating than just that of being thrust into the room?

Strikingly dimensional Hockney photo-collage: note several views of the sitter’s head in Christopher Isherwood talking to Bob Holman 1983. (Collection David Hockney)

“I’ll tell you,” Hockney says. “It takes time for the eye to move around the scene, just as it does in real life. So you have several aspects of Christopher which you remember as your eye moves back and forth. You can’t sweep quickly across that view of the Grand Canyon either: you’re forced to look at it slowly. There are as many pictures as your eye would find by looking across the canyon. And in that view of my hotel room, no lens on its own could give you the feeling of lying in bed looking around.”

Hockney finally throws in his stun grenade. “It’s directly related to cubism, I know that. And I’m a little bit turned on by that.”

Before readers’ eyes glaze over at the mention of the most baffling movement in modern art, take heart from Hockney’s own confession. “Cubism is difficult to grasp, even for me. I’ve looked at some cubist paintings for 25 years without understanding them. People said cubism led to abstraction but that’s another art-history swindle. Suddenly I see cubism differently, more clearly. And my experiments have led me to a couple of theories of my own…”

Photo-collage with the artist’s feet visible: My Mother, Bolton Abbey, Yorkshire, Nov 82 #4. (Collection David Hockney)

Later, at the artist’s Victorian studio in Kensington, Hockney was to expand on their implications. It is a bright, vast room, inspirationally cluttered: posters for his own work fill wallspace; a bust of his hero Picasso lodges high in the bookshelves; on the table sit some children’s toys, a tiny Pentax camera, copies of Middlemarch and a book comically titled Proust’s Binoculars. He is himself a study: red striped shirt, yellow watch and belt, the famous mismatched socks and mismatched frames for each lens of his spectacles. He has a 12-dollar price-tag dangling from his blue baseball hat. “Have I?” he says as if he doesn’t know.

He is over from LA, visiting for a fortnight, for his birthday, for the Kasmin show and to consult with Covent Garden on his designs for a Ravel/Stravinsky double bill next season, sets and costumes, too, this time. “I design opera because I’m interested. They don’t actually pay that well.”

A seven-foot canvas is in progress on one easel and a second is nearly finished on another, confirming that Hockney has not abandoned painting. In fact, he reveals that he has resumed painting this very week after a two-year break to pursue photography. The freshly primed canvases in his London studio testify to the urgency with which he wants “to deal with the ideas that are bubbling away”. He chain-smokes (Gitanes and Bensons by turns) as he expounds.

“This is my own thought, one which I’ve never read: that cubism has to do with identity” – David Hockney

“Have you been to the cubism exhibition at the Tate?” he suddenly enthuses about the summer’s major attraction, The Essential Cubism. “I’ve been seven times! Fantastic, fantastic. It’s all about closeness. When I first came out and saw the Francis Bacon tryptich just outside I suddenly went back to that distant view of the world which we call realistic! That’s what I’m only starting to grasp. Cubism is about another way of seeing the world, a truer way.

“And this is my own thought, one which I’ve never read: that cubism has to do with identity. Obviously it does, because when you look from more than one point of view the shape of things change as you move. It’s to do with you. My picture is not about the Grand Canyon but about you looking at the Grand Canyon.”

At this exciting crossroads in the artist’s own perception of the visual world, Hockney seems eager to air the thoughts bubbling in his mind and my ears happen to be nearest. He reaches for that book, Proust’s Binoculars, a study by the American scholar Roger Shattuck of the French novelist’s experiments in expressing the “miracle of vision” in prose. Hockney starts reading aloud about how we distinguish three basic ways of seeing the world when presented with a mutiplicity of images. (1) The cinematographic principle, which employs a sequence of separately insignificant differences to produce the effect of motion, the sensation of flux, of steady linear change. (2) The montage principle, which employs a succession of large contrasts to reproduce the disparity and contradiction that interrupt the continuity of experience. The director Sergei Eisenstein, Shattuck reminds us, stated tersely that “montage is conflict”. (3) The stereoscopic principle, which abandons the portrayal of motion in order to establish a form of arrest which resists time, yet enables us to discern pattern. It allows our binocular vision of mind to hold contradictory aspects of things in the steady perspective of recognition.

Hockney at his Kensington studio in London, July 3, 1983: so keen to deal with his new ideas, he reads aloud from Shattuck’s book about Proust while the toy parrot on his table listens. Behind him we see a freshly worked canvas, marking his return to painting. Photographed © by Shapersofthe80s

I find myself in the midst of an exhilarating tutorial from Hockney about notions which seem for him to be opening the doors to perception and with which he is plainly wrestling. He has always been an explainer about how we use our eyes, about the act of looking, and what he has recognised in Proust is his technique for showing the reader around his world, like a tour guide whose detailed descriptions legendarily go on for page after page. It is, Hockney asserts, identical to the way we view a cubist painting, the eyes darting from facet to facet, plane to plane, taking one snapshot after another. Hockney makes the observation, self-evident only with hindsight, that the act of looking around Proust’s world takes time – that spending time with Proust is about duration. And so, he is musing out loud, is cubism.

Few of us have read Proust’s 20th-century masterwork, A la recherche du temps perdu, which runs to 12 volumes in some editions. Hockney has, however, and was profoundly affected by it at the age of 21. It is impressive but by now unsurprising to hear that Hockney has read the epic twice. [Even among the literati, this is a rare achievement, though Booker Prize-winner Antonia Byatt is the only person I’ve met who has read it three times, once “in French”.] Hockney draws attention to the fact that for the Proust epic’s early English translations, editors turned for a title to Shakespeare’s resonant phrase, Remembrance of Things Past, which is more romantic than accurate. Strictly translated from the French and routinely applied to recent editions, Proust’s title is today rendered as In Search of Lost Time.

Like Proust’s prose, Hockney’s photo-collages mingle past and present. What is fascinating Hockney is how to inject the dimension of time into a work of art. “What I figured out was that you can’t explore a single photograph like a painting because it does not depict the passage of time. Time is what I’m concerned with putting in,” he says. “My new pictures are all about life going on around you. They are about duration. You can’t sweep quickly across them: you’re forced to look slowly. There are as many separate pictures as your eyes would find … it’s about the eye’s movement through time and your remembering each aspect of the view. Visually Proust’s descriptions are just like that.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that a single photograph is nothing but a glance. It cannot be objective. It is one-eyed, it has fixed perspective and this old way of seeing dominates movies, television and photography. My criticism is this: photography is like looking through a window but the world begins here, with me, not through the window. My feet don’t appear in my collages out of cuteness.”

What Hockney says he has done is to remove the window, like removing the void between a cinema screen and your seat.

Hockney in London, Jul 10, 1983: a new work looking very Picasso-esque, photographed by Shapersofthe80s

By tilting the camera down to include his feet and to the side to include his surroundings, there is a continuous link between viewer and subject. But by providing a composite selection of views he has broken with traditional one-point perspective and isn’t that what Picasso and Braque were doing with cubism 60 years ago?

This prompts me now to do a double-take at the new painting on its easel and I try to make a joke: “Er, doesn’t it look a bit like you-know-who?” To which Hockney replies: “I know. The danger is ending up with a poor pastiche of Picasso. Cubism is hard enough to grasp but it’s even harder to do. That’s what I’m learning now. But the moment you grasp it, you can’t give it up.”

When I return to the studio a few days later, again with my camera, another, larger canvas is almost completed. Hockney has returned, refreshed, to painting. Yet he makes one further revelation with utter simplicity. The reason why cubism has been overlooked since the experiments of Picasso and Braque in the early 20th century is because another invention being developed at the same time seemed then to be the most vivid depiction of reality: the cinema. Indeed the innovations of Chaplin and others between 1910 and 1920 were transforming Hollywood and creating a dramatic new visual language.

“Cubism isn’t finished,” Hockney says. “It’s too good, too true. We’ve seen its effects on posters but what we’ve not seen is its effect on TV and the movies. The cinema needs cubifying, I’m convinced. A cubist revolution has to come. Steven Spielberg knows what I mean. I think the time has come when the artist has to deal with these things.”

The Bradford genius clearly sees his mission to carry on where Picasso left off, to make a journey into cubism, into time and space. After theorising well into extra time, Hockney is earthbound enough to announce that his own work is often completely misinterpreted. “There are certain weaknesses, of course. I tend to make things charming, but why not? What do you think he does?” he asks, touching a toy parrot which instantly tilts and chirps on the table. “He charms you. That’s really my role: to chirp a bit and to charm.”

Text © Shapersofthe80s

At some future date, the original tape recorded interviews

with Hockney will be made available

❏ One sequel to this piece was that Melvyn Bragg pursued Hockney’s theme of wishing for a cubistic revolution in cinema by putting a cine camera into the artist’s hands for an edition of the British television arts series The South Bank Show. The film was broadcast on November 13, 1983. That month the artist also delivered a lecture titled On Photography in London

Hockney wielding his Pentax in London, July 10, 1983: having devoted two years to photography, in this his second week in Britain, a further new canvas in the studio confirms a return to painting. Photographed © by Shapersofthe80s

➢ The following related extracts from Hockney’s biography on his website make no mention of his cubismic epiphany in London. As my photographs show, the website is wrong in stating that he returned to painting the year after he actually did.

❚ 1982 – In an investigation of Cubism and pictorial space he starts experimenting with Polaroid composites. By May he has completed 150 works and opens a show in New York in June called Drawing with a Camera … In September he begins making photocollages using a Pentax 110 camera.

❚ 1983 – In the autumn he draws a series of revealing self-portraits almost every day for six weeks. In November he delivers a lecture, On Photography, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in which he argues for dispensing with Renaissance one-point perspective in favour of “many points of focus and many moments”, which more accurately reflect human perception.

❚ 1984 – After a break of almost four years Hockney begins painting again. The spring and summer are spent painting portraits in which he brings the model closer to the viewer, a development of his photographic experiments. Celia Birtwell, Christopher Isherwood, and David and Ann Graves are among his subjects.

➢ Visit the only authorised David Hockney website

➢ How Alain Sayag of the Pompidou Centre prompted Hockney’s adventure with Polaroids

❏ ABOVE – The artist explains his photocollages in this excerpt from the 1983 documentary David Hockney– Joiner Photographs by Don Featherstone.

➢ More photographic collages by David Hockney at leblogdesovena

➢ The biggest collection of Hockney’s work in the UK, collected by his late schoolfriend Jonathan Silver, and displayed in the monumental wool-spinning mill at the centre of the delightful 19th-century model village of Saltaire in Yorkshire, built by Sir Titus Salt for his workers. Well worth a detour

2004 ➤ The camera today?

You can’t trust it

Unreal: montage created electronically by the Guardian from two photos by David Sillitoe; image Lisa Foreman

2004 ➢ Hockney sparks a debate about an art form he believes is dying — from The Guardian

2009 ➤ Audio slideshow illustrating ‘David Hockney’s iPhone Passion’

2009 ➤ Audio slideshow illustrating ‘David Hockney’s iPhone Passion’

❏ LAWRENCE WESCHLER of The New York Review of Books discusses the new drawings that David Hockney has been making with the Brushes application on an iPhone. His piece “David Hockney’s iPhone Passion” was published on October 22, 2009. Alongside is one of the artist’s images of dawn over the North Sea mailed to the writer in North America as the sun rose over the Yorkshire coast. “This is a lovely fluid medium,” Hockney says.

[Image © David Hockney]

➢ VIEW the audio slideshow about David Hockney’s iPhone Passion

❏+++❏+++❏

2009 ➤ How to look properly at the world around us

❏ INVITED TO BE a guest editor of BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Dec 29, 2009, David Hockney tries to open presenter Evan Davis’s eyes on a tour of the countryside and seaside around his home town of Bridlington.

➢ VIEW the audio slideshow, Yorkshire Through

David Hockney’s Eyes

❏+++❏+++❏

2010 ➤ Hockney discusses his iPad art

➢ Hockney exhibit in Paris uses iPhones, iPad in place of canvas, until Jan 30, 2011 — David Hockney: Fleurs Fraîches is at the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent, Paris (+331 44 31 64 31)

➢ CBS report: celebrated British painter embraces the iPad

❏+++❏+++❏

2012 ➤ Hockney paints his first iPad portrait

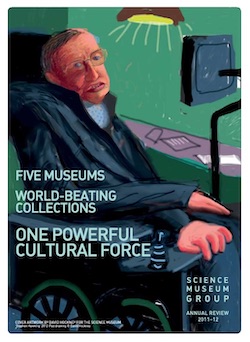

David Hockney at work on his iPad portrait of Stephen Hawking, showing from today at London’s Science Museum. Photograph © Judith Croasdell

Posted on March 20, 2012

➢ Britain’s best-known painter meets the world’s best-known scientist — Today’s Science Museum blog reports the outcome, a dazzlingly intimate birthday portrait of the wheelchair-bound cosmologist Prof Stephen Hawking. Renowned for his theories about black holes, he was made a celebrity in 1988 by his book, A Brief History of Time, which broke records by staying on the Sunday Times best-sellers list for 237 weeks.

The iPad portrait was captured by David Hockney during February at Hawking’s Cambridge office, using an app called Brushes, developed by Hockney. Rather like a sequence of timelapse photographs, an animated version of the iPad portrait is being screened in the special new 70th birthday display of the scientist’s personal memorabilia till Easter Monday.

This must be a unique and historic first to be able to watch an artist create a painting from start to finish in less than three minutes. The result is one of the most compelling and intimate portraits of Hawking, who looks serene and fascinating with strangely luminous violet eyes

2012 ➤ David Hockney and Damien Hirst go head to head with solo London shows

“Stump and logs as reminders of mortality … Hockney has transformed a humdrum wintry scene into a gateway to the afterlife” — David Hockney, detail from Winter Timber, 2009. Oil on 15 canvases. (Private Collection. © David Hockney. Photo credit: Jonathan Wilkinson)

➢ David Hockney makes dig at Damien Hirst’s use of assistants in notes for Royal Academy exhibition — from The Guardian

❏ A small note on the posters for David Hockney’s forthcoming exhibition at the Royal Academy contains a sly dig at another superstar artist about to launch a major exhibition. The note reads: “All the works here were made by the artist himself, personally.” In an interview with the Radio Times, Hockney confirmed that he had in mind Damien Hirst, whose £50m diamond and platinum skull will be the centrepiece of a Tate Modern exhibition in April, the first solo show of his work in a UK museum… / continued online

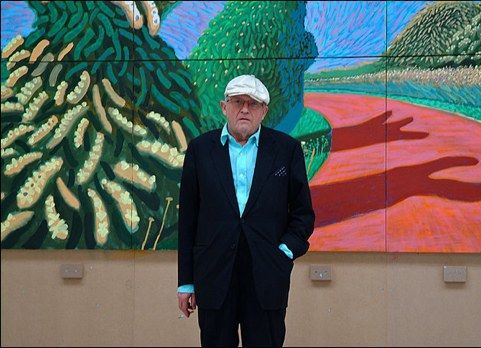

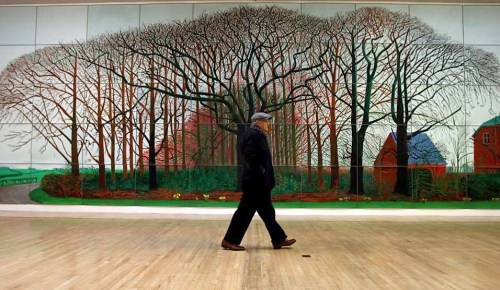

➢ David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture is the first major exhibition of new British landscape works by Hockney, plus his iPhone and iPad drawings and a series of multi-camera films. Runs at London’s Royal Academy, Jan 21–April 9, 2012 . . . On video Hockney, now aged 74, says: “It’s not a retrospective show. It’s a great deal of new work. Three or four years ago most of what’s in it didn’t exist . . . I’m confident there are a lot of new ideas about pictures, including television. They are very splendid galleries made for showing off very big pictures. I’m doing very, very big pictures which you wouldn’t do unless you’ve got a wall to put them on!”

Another reason to visit London: Hockney gifted Bigger Trees near Warter 2007 to the Tate gallery where it is now installed. The oil painting, his largest at that time, was made on fifty canvas panels and was executed outside, en plein air. It is not in the Royal Academy show. (Photograph EFE/Felipe Trueba)

2013 ➤ US premiere for Hockney’s 18-screen video The Jugglers in May

David Hockney (b 1937), still from The Jugglers, June 24th 2012 (2012). Eighteen-screen video installation, color, sound; 9 min ( © David Hockney. Image courtesy Hockney Pictures and Pace Gallery)

➢ Whitney to host US premiere of David Hockney’s video installation: The Jugglers, June 24th 2012

“ Filmed using eighteen fixed cameras, this multiscreen tableau shows a group of jugglers as they move in a procession across a grid of 18 screens. The figures, dressed in black and juggling brightly colored objects, perform in front of a pink wall and on a blue floor, creating a vibrant, colorful composition whose energy is echoed by a lively musical soundtrack. Hockney’s creation of a composite image from multiple perspectives places the choice of where to look with the viewer, demonstrating his ongoing interest in how technologies can open up new ways of looking at, and making, images. The exhibition runs May 23–Sept 1, 2013. ”

❏ The 600,000 visitors to A Bigger Picture, last year’s massive show at the Royal Academy in London, were able to view several earlier examples of Hockney’s experiments with multi-screen videoworks – some exterior journeys, some indoor performances – in a gallery dedicated to screening them. They pursue his exploration of cubist ideas and our ways of seeing so that their scale onsite tends to have a visceral impact. In 2007 Hockney began experimenting with a set of nine synchronised HD video cameras attached to a rig on his jeep which drove slowly through the lanes of Yorkshire. He claimed: “A single camera isn’t very good at showing landscape, but the nine cameras are.”

Each camera was set at a different angle, and many were set at different exposures. In some cases, the images were filmed a few seconds apart, so the viewer is looking, simultaneously, at two different points in time. A single screen directs your attention; you look where the camera was pointed. With multiple screens, you choose where to look.

After viewing the result simultaneously on 18 screens abutting each other in a wide panorama, one journalist marvelled: “They make me feel I have never seen a tree before.” “Yes,” Hockney replied emphatically. “There’s a lot more to be seen.” During the summer of 2012, Hockney was reported to be back in the lanes of Yorkshire shooting more footage.

➢ The Parisbreakfast blog documents the videos screened at Hockney’s RA exhibition in 2012

2013 ➤ Hello again to California

Hockney left the countryside of Yorkshire in June 2013 to return to live in California. Within months he was exhibiting his latest work in San Francisco…

➢ A Bigger Exhibition reviewed at Examiner.com

❏ “ Whether executed in oil, acryllic, watercolor, charcoal or as an Ipad drawing, on canvas or on single or multiple sheets of paper, Hockney’s landscapes – his En Plein Air (Outdoors) works – offer viewers a sumptuous vision of nature, and often one that chronicles the passage of time.

To convey multiple views of the forest in winter, spring, summer and fall in a totally different medium, Hockney made digital videos of Woldgate Woods in East Yorkshire, also in 2010 and 2011. He used nine cameras simultaneously to create what he calls a “Cubist movie” noting he’s not “anti-lens, he’s anti a single lens!” The resulting videos are displayed on nine flat-screen monitors, allowing viewers to be “stopping by woods on a snowy evening” or summer day, to watch the changing light and perspective…” / Continued online

David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition is at the de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, October 26–January 20 2014.

I remember vividly the impact reading that Face interview made on me 30 something years ago. Mind boggling.

Thanks, John. My three meetings with Hockney that week were lucky and life-enhancing! – DJ

Pingback: David Hockney's Cubist Photography | ShahidulNews

Pingback: Beyond Fiction: Artist Research | Inwit

Pingback: Different Perspectives and Constructing Essay Questions. – delargyphotography

Pingback: Time Space – Tuong Bach Pham